Piececlopedia: Rook

Historical notes

Originally Called a Chariot

Except for gaining the ability to castle, the Rook has remained the same since Chaturanga, which is widely regarded as the first form of Chess. According to Chess historians, this piece was originally known as a chariot. Duncan Forbes says that chariots were called Roka

or Ratha

in Sanskrit. (The History of Chess, 1860, Page 38) H.J.R. Murray says its original name was ratha, which is Sanskrit for chariot. He notes that this is pronounced răt-ha, not rath-a. (A History of Chess, 1913, Note on the Transliteration of Sakskrit, Persian, and Arabic Words

, Page 19) Notably, the piece is known by names meaning chariot in Chinese Chess and Korean Chess and as Flying Chariot (Hisha) in Shogi, the Japanese form of Chess, and each of these use the 車 pictograph for a chariot. In Versus de scachis, a 10th century Latin poem about Chess, it says, as paraphrased by H. J. R. Murray in A History of Chess, the Rook (rochus), or rather the Margrave (marchio) in his two-wheeled chariot, occupies the corner squares

(Page 498). The Italian figurine piece shown here from the late 11th century, which is part of a full collection of ivory pieces at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, also shows the piece as a chariot. These geographically diverse representations of the piece as a chariot help establish that it was also called a chariot in the original game. The British Museum has a 7th to 8th century Chariot piece from Nishapur, Iran that may have been used in Chatrang, and the Afrasiab Chessmen, the earliest set of Chessmen ever found, includes some charioted pieces.

The Name of Rukh

When the Persians got Chess from India, they called it a rukh. With regard to the word rukh, Forbes wrote in 1860,

The latter term, as well as our own Rook, are evidently derived from the Sanskrit Roka; although neither the Persians nor ourselves, in all probability, have ever known or thought of its original meaning. Sir William Jones derives the Persian Rukh from the SanskritRatha,a chariot, pronounced Roth in Bengali. This derivation is inadmissible for two reasons; in the first place it is too far-fetched; and, secondly, the word Ratha is never mentioned in the ancient account of the Chaturanga. (Page 40-41)

In other words, Forbes is saying that Ruhk derives from the Sanskrit word for boat, which is Roka, not from the Sanskrit word for chariot, which is Ratha. In favor of transliteration rather than translation, Sir William Jones (1746 – 1794) says, It were in vain to seek an etymology of the word rook in the modern Persian language; for, in all the passages extracted from Firdausi, and Jami, where rokh is conceived to mean a hero or fabulous bird, it signifies, I believe, no more than a cheek or face

(p. 5). Jean-Louis Cazaux has reported on a more recent scholar, an Italian named Antonio Panaino with an expertise in Persian, who has claimed in a work called La novella degli scacchi e della tavola reale, that ruhk meant cheek in Persian. Even if transliteration is what happened, this does not mean that the Persians understood the piece to be a cheek any more than modern day English speakers understand the Rook in Chess to be a type of old world crow (Corvus frugilegus), which the English word rook also means.

In favor of a transliteration from Roka rather than from Ratha, Roka does seem more phonetically similar, at least going by the Latin letters we are using to write these words. I presume the ancient account of the Chaturanga

Forbes refers to is the one that Jones translated and wrote about in The Indian Game of Chess. Evidently, what he translated was the rules for the four-player version Chaturaji, in which the piece is indeed called a boat. Since the Persians had the two-player version, it is possible that they learned of the game by a different description that did call the piece a chariot. Since one of the problems with ancient documents is that many get lost, we can't say for sure what description of the game the Persians first got. Jones apparently got the idea of Ratha being used for Chariot because the name Chaturanga refers to the four arms of the military, of which chariots would be one, related variants, such as Burmese Chess and Chinese Chess call it a chariot, and the Sanskrit word for chariot is Ratha. In fact, he does argue that the original piece was a chariot, saying,

I cannot agree with my friend Radhacant, that a ship is properly introduced in this imaginary warfare instead of a chariot, in which the old Indian warriors constantly fought; for, though the king might be supposed to sit in a car, so that the four angas would be complete, and though it may often be necessary in a real campaign to pass rivers or lakes, yet no river is marked on the Indian, as it is on the Chinese chess-board; and the intermixture of ships with horses, elephants, and infantry embattled on a plain, is an absurdity not to be defended. (p. 5)

Murray favors the idea that Ruhk is a translation of a word meaning chariot. He acknowledges that rukh could also mean a cheek, or a fabulous bird, or maybe even hero in Persian, but he maintains that in reference to the Chess piece, it meant chariot, saying, There can be no doubt that the chess-term Rukh simply meant chariot

(A History of Chess, 1913, Chapter VIII. Chess in Persia Under the Sasanians

, Page 160) However, he says further in the same paragraph, Although rukh has never been the ordinary word for chariot in Persian, there is some evidence to show that it did bear that meaning both in Persian and Arabic.

(Page 160). He cites Vuller's Persian Lexicon as saying that araba, the common Arabic word for chariot, was another word for rukh. He also cites Arabic-Latin glossaries in which rukhkh means chariot and Spanish glossaries indicating that the word rukhkh was in common use among the Moors in Spain in the sense of chariot.

Since this evidence suggests that even the Arabs knew the piece was a chariot and used the Persian word for the piece to mean chariot, this also stands as evidence that rukh was a Persian word for chariot. Additionally, Davidson cites the Burhani-Qati, a Persian dictionary that gives the meaning of chariot to rukh. (Davidson, A Short History of Chess, 1949, Page 46) However, the Encyclopedia Iranica's article on BORHĀN-E QĀṬEʿ questions its reliability.

Davidson suggests that this word originally referred to a soldier or hero, and that it acquired the meaning of chariot only by extension, as in a chariot driver being the hero of a battle. But Murray points out that no one has shown that rukh was ever used where one would expect the usual Persian word for hero. Murray rejects the theory that it meant hero and maintained that it meant chariot.

When the Arabs learned Chess from the Persians, they kept the name rukh. As indicated above, they may have understood this to mean chariot. However, Davidson cites the Encyclopedia of Islam as saying that the rukh in chess meant the monstrous bird of that name.

But he also claims that the encyclopedia is wrong, because it is an adaptation of a Persian word, and rukh never meant bird in Persian. (Davidson, A Short History of Chess, 1949, Page 45) Davidson may be mistaken about this, as the Wikipedia page on the mythical bird known in English as a Roc gives ruḵ as its Persian name and mentions that rukh is a common Romanization of this name. Additionally, Davidson says the Arabic portrayal of the piece with two projections

was a symbol of the two-headed bird, for whether the Arabs derived the word from the name of the bird or whether they simply carried over the Persian word forheroorchariot,the fact that their mythology did include a two-headed rukh made such a representation obvious. (Davidson, Page 47)

When looking for references to a two-headed roc, though, the oldest reference I found was a 1958 movie called The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. While the movie poster does show a two-headed roc, my search through the story of Sinbad in the Arabian Nights did not turn up any description of the roc as having two heads. Since Davidson wrote in 1949, his reference of a two-headed roc would be even earlier.

One piece of evidence that might support this theory is that la roque de Fréteval does have a face on each side. However, the earlier Shatranj piece from 9th to 12th century Nishapur does not, and the even earlier figurine piece from Nishapur, which would have been in Persia, was of a chariot. Also, it's possible that each face on the Fretevel piece is a horse, which would fit with the idea that it represents a chariot.

Portrayed as a Tower

When the piece made its way to Europe, it became common to represent it as some kind of tower, similar to how it is now portrayed in the Staunton set. While some have attributed this to a tower being carried on the back of an elephant in some old pieces, this was not the same piece. Duncan Forbes accounts for this by the linguistic similarity between the name and Italian words for fortress. With the explanation just mentioned in mind, he rhetorically asks,

Is it not much more likely, then, that the Italians were the first that brought the figure of the tower on the board — not from theElephant and Castle,but simply because the word rocca or rocco does mean a castle or fortress in their language? (The History of Chess, 1860, Page 161)

Indeed, rocca does mean fortress in Italian. At that time, mobile towers were popular instruments of war. (The Dabbabah is another Chess piece named after this mobile tower.) This may have led to the tradition of calling the piece a tower. It was called torre in Spanish, tour in French, Toren in Dutch, and Turm in German. English merely tranliterated rukh into Rook, but even English speakers began representing the piece as a tower, and many English speakers frequently call the piece a Castle.

Jean-Louis Cazaux speculates that due to phonetic similarity, the name of this piece was taken to mean rock when the game was introduced to Europe. Etymologically speaking, the word rock is related to the Old North French roque and the Italian rocca. According to a different Italian-English dictionary than linked to above, rocca can mean either fortress or rock. According to Wiktionary, rocca is Latin for rock. However, representations of the piece, such as those Cazaux has on his Earliest European chessmen page do portray it as some kind of fortress rather than just a mere rock.

Based on these images, including the one displayed here in a larger size from a different source, it looks like the shape of the piece played a role in its portrayal as a fortress. Like the earlier piece, the German piece displayed here has two projections, but they are now turrets of a fortress. As the idea of it being a fortress took over, the number of turrets changed, and it eventually became the single-turreted tower we usually recognize as the Rook.

Movement

The Rook moves an arbitrary number of spaces in any orthogonal direction. It may not pass over occupied spaces, and it ends its move by occupying an empty space or by capturing an enemy piece.

While orthogonal literally means right-angled and originally refers to ranks and files being perpindicular to each other, its meaning has been stretched in Chess variants to refer to movement that follows the natural contours of the board. The detail that is the same for most boards is that when each space has a shape, orthogonal directions proceed through the opposite sides of spaces. In this case, orthogonal may be understood along the lines of orthodox, where ortho- means something like right or official rather than being at 90 degrees to each other. Accordingly, orthogonal movement would be movement along the correct angles, these being the ones in alignment with the contours of the board.

On the Chess board

On the Chess board, the Rook's move takes it in a single direction through the sides of square spaces. The sides of a square are its edges. The directions it may move correspond to the two axes of the board. The vertical axis is the file the Rook starts from, and the horizontal axis is the rank it starts from. Each move moves it along the same rank or the same file. The diagram below shows the full range of movement for White's Rook, and it shows that Black's Rook is blocked by two Pawns. It can capture the White Pawn, but it cannot capture its own.

On a 3D Cubic board

On a 3D board, the Rook's move takes it in a single direction through the sides of cubic spaces. The sides of a cube are its faces, each one of which is a square. The directions it may move correspond to the three axes of the board. The x-axis is the file the Rook starts from, the y-axis axis is the rank it starts from, and the z-axis is the level it starts from. Each move changes its position along only one axis.

On a hexagonal board

On a hexagonal board, its movement proceeds in a straight line through the sides of hexagonal spaces. Since a hexagon has six sides, the directions it may move do not all correspond to the dimensional axes. Depending on the orientation of the hexagons, a Rook can move along either the vertical axis or the horizontal axis, but not both. When the board is oriented to allow the Rook to move straight forward and backward along the vertical axis, its directions of movement correspond to the even hours on a clockface. When it is oriented to allow the Rook to move left or right along the horizontal axis, its directions of movement correspond to the odd hours on a clockface.

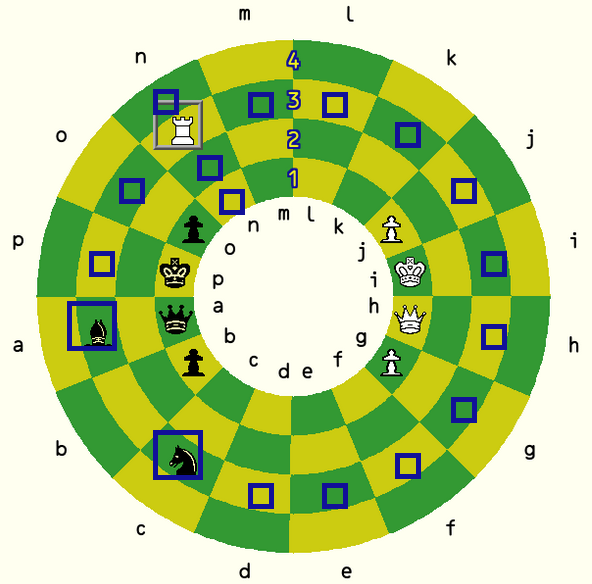

On a Circular board

On a circular board, its movement proceeds through the opposite sides of spaces, as it does on the boards mentioned above. But on a circular board, this can take it in a circle instead or in a straight line, allowing its move to return to its original position unless it is blocked, or there is a rule against null moves. Instead of being based on Cartesian coordinates, its movement is based on polar coodinates. It may move inward or outward along the radius it is on, or it may move clockwise or counterclockwise along the circle it is on. In the diagram below, the Rook at n3 may capture the Bishop on a3 by moving counterclockwise toward it, or the Knight on c3 by moving clockwise. It may not move to b3, because it is blocked in both directions. It may move along the n file, but the n file does not lead to the f file.

On a Spherical board

On a spherical board, its movement proceeds through the opposite sides of spaces, as it does on the boards mentioned above, taking it along a line of longitude or latitude. Whichever way it goes, its move may loop back on itself if no pieces are in the way and there is no rule against it. In the diagram below, the Rook can capture the Bishop by moving through the South Pole, or it can capture the Knight by moving through the North Pole and continuing south. The Rook may not go to g2, because it is blocked both ways, but it may go to g3 by going east, and it may also capture the Pawn on h3 by moving east. It cannot reach these spaces by moving west, because the White Knight blocks its movement in that direction.

Piece Graphics

These graphics are available for use in diagrams or for playing games online. Click on an image to view the full piece set it belongs to.

Chess Rook images

Xiangqi Chariot images

Shogi Flying Chariot images

References

Forbes, Duncan. The History of Chess: From the Time of the Early Invention of the Game in India Till the Period of Its Establishment in Western and Central Europe, 1860. Buy The History of Chess on Amazon.

Murray, H. J. R. A History of Chess, 1913. Buy A History of Chess on Amazon.

Davidson, Henry A. A Short History of Chess, 1949. Buy A Short History of Chess on Amazon.

This is an item in the Piececlopedia: an overview of different (fairy) chess pieces.

Written by Fergus Duniho.

WWW page created: September 9, 1998.

Last updated: January 22, 2025.